Page 39 - Manual of Roman Everyday Writing Volume 2: Writing Equipment

P. 39

38| MANUAL OF ROMAN EVERYDAY WRITING VOLUME 2: WRITING EQUIMENT | 39

Further reading:

Božič and Feugère 2004, 28–31; Gostenčnik 1996; Manning 1985, 85–87;

Mikler 1997, 25–27 with plates 15–17; Schaltenbrand Obrecht 2012

Selected ancient literary evidence:

In Plautus’ Bacchides (4.4.74–112), Chrysalus dictates a letter to be written

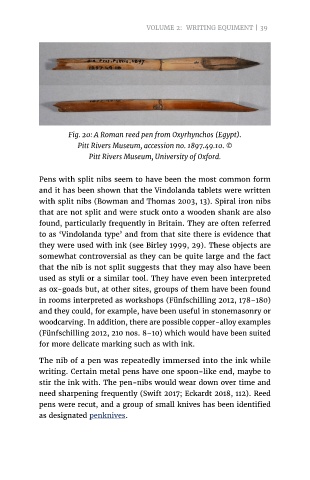

by Mnesilochus to his father, with a stylus on wax tablets. Another letter is Fig. 20: A Roman reed pen from Oxyrhynchos (Egypt).

written with stylus on wax by Byblis in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (9.522–525). Pitt Rivers Museum, accession no. 1897.49.10. ©

Seneca (Clem. 1.14) uses ‘taking the stylus’ as a metaphor for ‘to disinherit’; Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Pliny the Elder (NH 34.139) claims that after the expulsion of the kings of

Rome, styli were not made from iron; Quintilian (Inst. or. 10.4.1) says that Pens with split nibs seem to have been the most common form

deleting is just as important a function of the stylus as is writing; Horace and it has been shown that the Vindolanda tablets were written

(Sat. 10.72–74) explains that good poetry is achieved by erasing (stilum with split nibs (Bowman and Thomas 2003, 13). Spiral iron nibs

vertere) frequently. Symphosius wrote a riddle about the stylus, which he that are not split and were stuck onto a wooden shank are also

calls graphium (Aenigmata 1). found, particularly frequently in Britain. They are often referred

to as ‘Vindolanda type’ and from that site there is evidence that

they were used with ink (see Birley 1999, 29). These objects are

Ink pen (calamus/harundo) somewhat controversial as they can be quite large and the fact

that the nib is not split suggests that they may also have been

Roman pens were used from the 1st century BCE onwards to write used as styli or a similar tool. They have even been interpreted

with black or red ink on papyrus, ostraca, wooden leaf tablets, the as ox-goads but, at other sites, groups of them have been found

outside of wax tablets and, in rarely preserved cases, also on metal in rooms interpreted as workshops (Fünfschilling 2012, 178–180)

(Reuter and Scholz 2004, 15). and they could, for example, have been useful in stonemasonry or

woodcarving. In addition, there are possible copper-alloy examples

Pens were made of reed or metal, mainly bronze/copper-alloy

rolled to form a small tube, between c.10–19 cm long, with one (Fünfschilling 2012, 210 nos. 8–10) which would have been suited

bevelled end cut to create a split nib. Rare examples made of iron, for more delicate marking such as with ink.

silver, bone and ivory have been found (Božič and Feugère 2004, 37 The nib of a pen was repeatedly immersed into the ink while

and e.g. Jilek 2000 with photos of a bone pen). It is unclear when writing. Certain metal pens have one spoon-like end, maybe to

feather quills (pennae) were first used for writing but their use is stir the ink with. The pen-nibs would wear down over time and

not attested before the 6th or 7th century CE (Božič and Feugère need sharpening frequently (Swift 2017; Eckardt 2018, 112). Reed

2004, 37 and see Anonymus Valesianus II 79). Reed pens must pens were recut, and a group of small knives has been identified

have been the most commonly used kind and metal pens are in as designated penknives.

general very rare.