Page 46 - Manual of Roman Everyday Writing Volume 2: Writing Equipment

P. 46

46| MANUAL OF ROMAN EVERYDAY WRITING VOLUME 2: WRITING EQUIMENT | 47

Fig. 27: Ink tablet from Vindolanda (UK): letter from

Niger and Brocchus to Flavius Cerialis, late 1st/early 2nd

century CE. Tab. Vindol. 248, British Museum, museum

no. 1980,0303.21. © Trustees of the British Museum.

examples, giving an intriguing insight to life in the camp, especially

in the period 90–120 CE. A few Vindolanda tablets mention the word

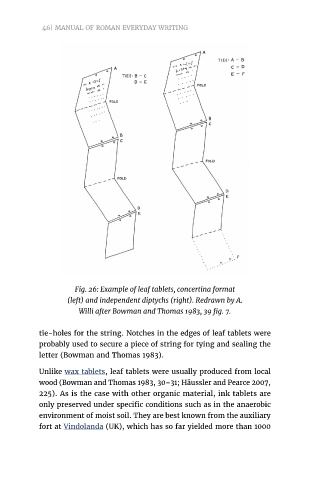

Fig. 26: Example of leaf tablets, concertina format tilia referring to an ink tablet (esp. Tab. Vindol. 589).

(left) and independent diptychs (right). Redrawn by A.

Willi after Bowman and Thomas 1983, 39 fig. 7. Only a handful of leaf tablets were known before the Vindolanda

tablets were first discovered in the 1970s. Ever since, scholars have

become more aware of them and small numbers of finds are now

tie-holes for the string. Notches in the edges of leaf tablets were

probably used to secure a piece of string for tying and sealing the known from many sites, particularly in the UK, albeit often less

letter (Bowman and Thomas 1983). well preserved than the ones from Vindolanda (Hartmann 2015).

The auxiliary fort at Luguvalium (Carlisle) with over 130 tablets

Unlike wax tablets, leaf tablets were usually produced from local represents another hotspot (Tomlin 1998).

wood (Bowman and Thomas 1983, 30–31; Häussler and Pearce 2007,

225). As is the case with other organic material, ink tablets are From late antiquity and other parts of the empire slightly different

only preserved under specific conditions such as in the anaerobic ink tablets are preserved: the tablets from Kellis (Dakhleh Oasis,

environment of moist soil. They are best known from the auxiliary Egypt) dating to the 4th century CE and the Tablettes Albertini,

fort at Vindolanda (UK), which has so far yielded more than 1000 45 tablets found on the Tunisian-Algerian border west of Gafsa,

dating to the 5th century CE. The latter contain legal contracts