Page 64 - Manual of Roman Everyday Writing Volume 2: Writing Equipment

P. 64

64| MANUAL OF ROMAN EVERYDAY WRITING VOLUME 2: WRITING EQUIMENT | 65

inscriptions. Traditionally, scholars considered their use to be tied Other surfaces, objects and materials

to military contexts. Military lead tags are for example known from

the legionary camp in Usk (UK, see Hassall 1982, 51). But finds People in Roman times scribbled on all kinds of surfaces and objects

are in fact more frequent from the context of commerce and the that were not primarily intended or purpose-made for writing. This

production of goods, e.g. in Kalsdorf (Austria, see Römer-Martijnse includes instances of which no, or only indirect, evidence survives,

1990) or Sisak (Croatia, see Radman-Livaja 2014). Most of the finds such as tree bark (Kruschwitz 2010) or textiles. The latter were

date to the 1st–3rd centuries CE. used by the Etruscans and, according to Livy, for keeping lists of

magistrates in the temple of Moneta in Rome (e.g. Liv. 4.20.8).

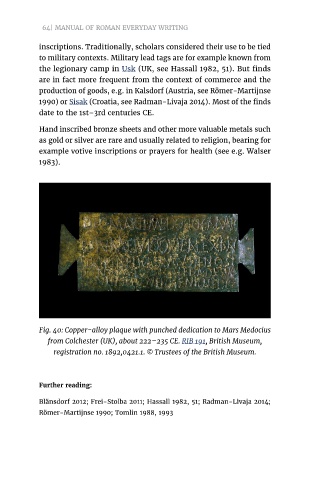

Hand inscribed bronze sheets and other more valuable metals such Scribbles were also made with chalk and charcoal (see e.g. Mart.

as gold or silver are rare and usually related to religion, bearing for 12.61.7–10) of which exceedingly few examples survive.

example votive inscriptions or prayers for health (see e.g. Walser

1983). Hundreds of thousands of graffiti and dipinti have been preserved on

more durable materials including those commonly associated with

monumental inscriptions such as stone and metal, containing simple

marks and names as well as administrative notes and even poetry.

Many readers of this manual will be familiar with the numerous

inscriptions discovered on the walls of public and private spaces

in Pompeii (see e.g. Kruschwitz 1999, 235–44; Benefiel 2015) but

such texts can be found across the empire.

Fig. 40: Copper-alloy plaque with punched dedication to Mars Medocius

from Colchester (UK), about 222–235 CE. RIB 191, British Museum,

registration no. 1892,0421.1. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Further reading:

Blänsdorf 2012; Frei-Stolba 2011; Hassall 1982, 51; Radman-Livaja 2014; Fig. 41: Wall graffito from the Roman villa in Wagen,

Römer-Martijnse 1990; Tomlin 1988, 1993 Salet (Switzerland), reading Mas/clus / perm/isit na/

to tra/n(scribere…?) (‘Masclus allowed his son to

write(?)…’). © Kantonsarchäologie St. Gallen.